Guns have a long, winding history in America. A story by The Marshall Project published this week revealed that when it comes to enforcing gun laws, Black men pay the price — especially in Chicago.

The legal system in Illinois that has led to the incarceration of thousands is more than 60 years in the making — rooted in politics that are inseparable from race, crime and power.

When Illinois codified its criminal code in the early 1960s, it included a statute called “unlawful use of weapons,” a confusing name for a series of laws focused primarily on weapons possession, not use.

Years of racial uprisings and increasing gun violence nationwide had politicians in an uproar. By 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a “war on crime” and increased federal funding for police departments.

The following year, Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley vented to President Johnson about the lack of progress on gun control.

In a late evening call to Johnson, Daley expressed frustration with “civil rights demands,” “open and armed rebellion,” and the potential “breakdown of law enforcement” to combat “lawlessness” — which he felt was a “damn serious situation,” across the country.

“Outside the suburbs, in the city, we have control, but what the hell — you go out to all around our suburbs, and you’ve got people out there, especially the non-White, are buying guns right and left,” Daley told the president. “Shotguns and rifles and pistols and everything else. There’s no registration. … There isn’t a damn thing, and you know, something has to be done under the gun law.”

Although Daley wanted a national gun registry, it never materialized nationally.

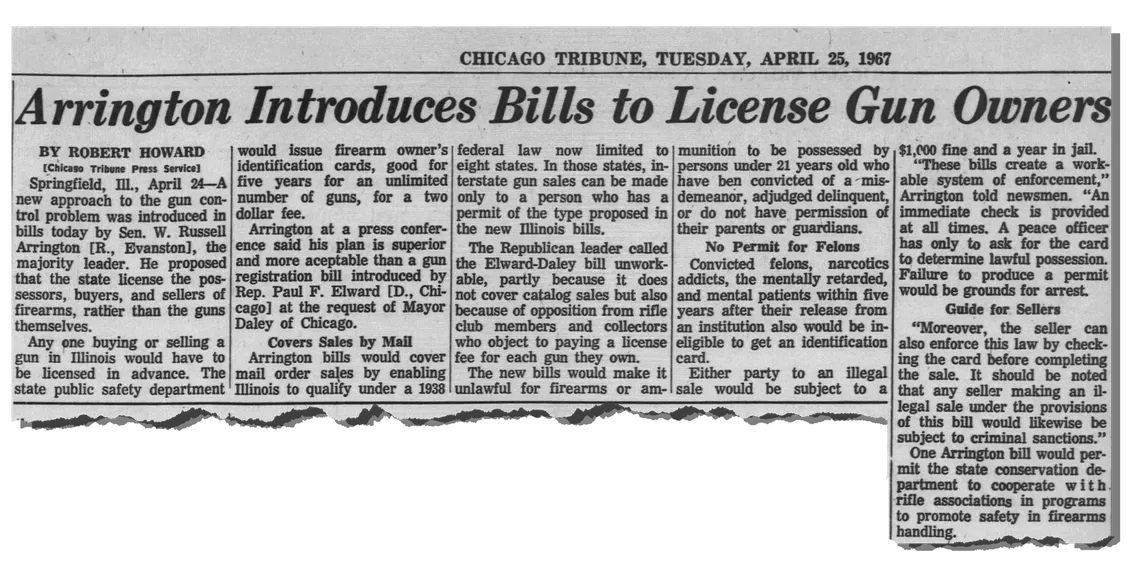

In 1968, a bipartisan law requiring residents to obtain a Firearm Owners Identification Card in order to legally own a gun took effect. The Republican lawmakers who proposed the bill saw it as a compromise, since the Illinois State National Rifle Association did not want a statewide handgun registry.

The bill gained steam when officials pitched its ability to aid police in, as one Chicago Tribune news article described, “large scale assaults in racial disturbances.” While the state stopped short of a comprehensive registry, the city of Chicago passed its own.

Some Black lawmakers in Chicago decried the new gun regulations as racist, according to articles published in the Chicago Defender, the city’s historic Black newspaper.

Chicago Alderman Sammy Rayner was one of those concerned about the city law passed under Daley requiring residents to register their guns.

“Information has come to me that the ordinances are part of a grand conspiracy to control the Black community. One thing is true; it would enhance the position of the authorities if they knew the whereabouts of all guns controlled by Black people,” Rayner told the Defender. “Gun control, ‘mob action’ arrests with high bonds, and ‘field contact’ interviews all go together to contain the Black ghetto.”

Roy Innis, a Black nationalist at the time, also felt the enforcement would lead to racial disparities. “White racist police and judges and prosecutors will be enforcing these laws, and we know how laws are now implemented,” he wrote to the paper. “Black people will be disarmed, and [W]hite people will not be.”

Illinois lawmakers weren’t the only ones pushing for a version of gun control meant to curtail the burgeoning Black Power movement. In California, in direct response to the Black Panthers legally carrying guns on state capitol grounds, officials swiftly passed a law banning openly carrying loaded firearms.

Following the 1968 assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, Congress enacted the Gun Control Act, with NRA support. The laws regulated interstate gun sales, included a 21-and-up age requirement to purchase firearms, and prohibited people with felony convictions from legally owning guns.

That same year, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a pivotal opinion in Terry v. Ohio, declaring that police could stop and search someone suspected of committing a crime and being armed — without violating the Fourth Amendment right to unlawful search and seizures. Today, this practice is commonly referred to as a Terry stop.

“[It] makes perfect sense that in a racist, apartheid-like society, you're going to have laws that restrict access to dangerous weapons to keep the powerless, powerless,” said Adam Winkler, a Second Amendment historian and law professor at UCLA. “We have definitely seen a racist history of gun laws — not to say that all gun laws are racist,” he said.

Despite the racial disparities in Chicago’s gun law enforcement, state legislation does not explicitly state police should target Black communities. Winkler says this is an example of how many modern gun laws, passed with the intent to keep the public safe, are ‘race neutral.’

“Chicago is a really telling example where there is a legitimate gun violence problem and legitimate efforts to try to correct that problem — but they run headlong into American traditions of racial discrimination,” he said.

In Illinois, the 1960s crime wave led to the passage of the Armed Violence Act, a sentencing enhancement that includes possessing a gun while committing a felony crime, regardless of whether the gun was fired or if the crime was violent. In the ‘80s, a new Chicago mayor, Jane Byrne, enacted an ordinance that effectively banned any new handguns in the city. At the height of the “superpredator'' era in the mid-‘90s, state lawmakers increased the penalty for illegal gun possession from a misdemeanor to a felony that excluded an option for parole. Shortly after the new millennium, lawmakers expanded the three-strikes Habitual Criminal Act to include a statute specifically related to serious weapon crimes, which included possession.

Nearly a decade later, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Chicago’s handgun ban, resulting in state lawmakers passing a concealed carry law.

All together, these laws have acted like nesting dolls, creating increasingly punitive sentences over time.

Today, prison data in Illinois shows that the majority of people incarcerated for crimes related to unlawful use of weapons, armed violence, and armed habitual criminal offenses are Black men.

A previous version of this story misstated the parameters of California's open carry ban. The 1967 Mulford Act banned openly carrying loaded firearms in public by civilians.