If Black Americans died at the same rates as White Americans, in 2019 about 294,000 Black Americans would have died.

Here's what those deaths would look like arranged by age.

But, due to racial disparities in mortality, Black Americans die younger at almost every age. Here are actual deaths in 2019: over 72,000 more Black Americans died at younger ages.

Once Americans reached their mid-80s, Black people began to have lower death rates than Whites, with about 11,000 fewer Black deaths in 2019.

In total, that adds up to over 355,000 Black deaths in 2019 — 1 in 5 of which happened earlier than expected for White Americans.

The biggest inequality affected Black infants, who had more than twice the White infant mortality rate. In 2019, almost 3,600 more Black babies died before their first birthday.

Black Americans die at higher rates than White Americans at nearly every age.

In 2019, the most recent year with available mortality data, there were over 62,000 such earlier deaths — or one out of every five African American deaths.

The age group most affected by the inequality was infants. Black babies were more than twice as likely as White babies to die before their first birthday.

The overall mortality disparity has existed for centuries. Racism drives some of the key social determinants of health, like lower levels of income and generational wealth; less access to healthy food, water and public spaces; environmental damage; overpolicing and disproportionate incarceration; and the stresses of prolonged discrimination.

But the health care system also plays a part in this disparity.

Research shows Black Americans receive less and lower-quality care for conditions like cancer, heart problems, pneumonia, pain management, prenatal and maternal health, and overall preventive health. During the pandemic, this racial longevity gap seemed to grow again after narrowing in recent years.

Some clues to why health care is failing African Americans can be found in a document written over 100 years ago: the Flexner Report.

In the early 1900s, the U.S. medical field was in disarray. Churning students through short academic terms with inadequate clinical facilities, medical schools were flooding the field with unqualified doctors — and pocketing the tuition fees. Dangerous quacks and con artists flourished.

Physicians led by the American Medical Association (A.M.A.) were pushing for reform. Abraham Flexner, an educator, was chosen to perform a nationwide survey of the state of medical schools.

He did not like what he saw.

Published in 1910, the Flexner Report blasted the unregulated state of medical education, urging professional standards to produce a force of “fewer and better doctors.”

Flexner recommended raising students’ pre-medical entry requirements and academic terms. Medical schools should partner with hospitals, invest more in faculty and facilities, and adopt Northern city training models. States should bolster regulation. Specialties should expand. Medicine should be based on science.

The effects were remarkable. As state boards enforced the standards, more than half the medical schools in the U.S. and Canada closed, and the numbers of practices and physicians plummeted.

The new rules brought advances to doctors across the country, giving the field a new level of scientific rigor and protections for patients.

But there was also a lesser-known side of the Flexner Report.

Black Americans already had an inferior experience with the health system. Black patients received segregated care; Black medical students were excluded from training programs; Black physicians lacked resources for their practices.

Handing down exacting new standards without the means to put them into effect, the Flexner report was devastating for Black medicine.

Of the seven Black medical schools that existed at the time, only two — Howard and Meharry — remained for Black applicants, who were barred from historically White institutions.

The new requirements for students, in particular the higher tuition fees prompted by the upgraded medical school standards, also meant those with wealth and resources were overwhelmingly more likely to get in than those without.

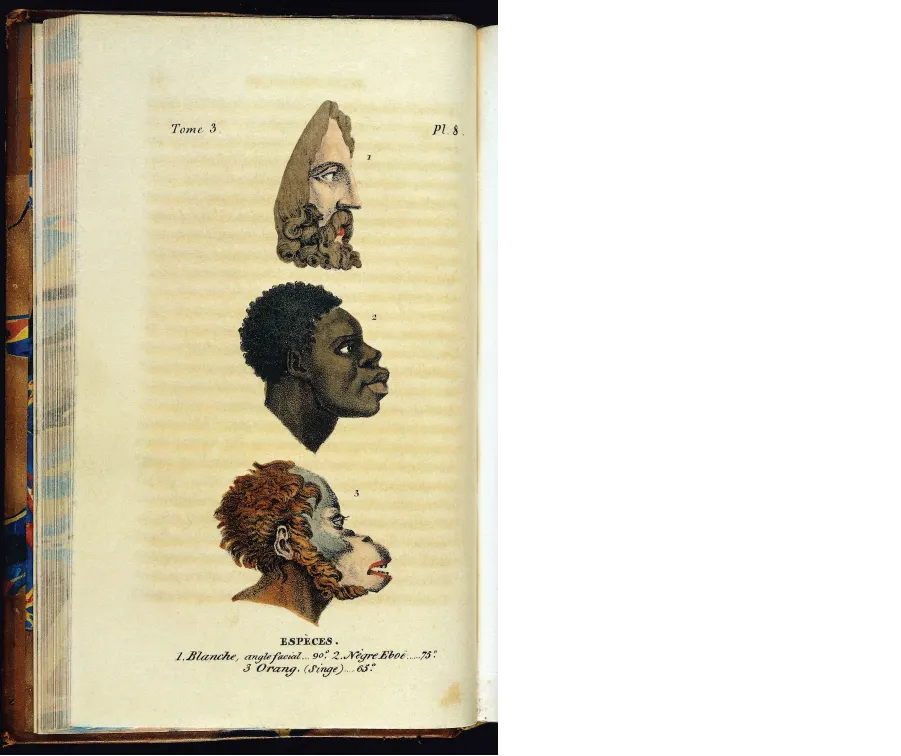

The report recommended that Black doctors see only Black patients, and that they should focus on areas like hygiene, calling it “dangerous” for them to specialize in other parts of the profession. Flexner said the White medical field should offer Black patients care as a moral imperative, but also because it was necessary to prevent them from transmitting diseases to White people. Integration, seen as medically dangerous, was out of the question.

The effect was to narrow the medical field both in total numbers of doctors, and the racial and class diversity within their ranks.

When the report was published, physicians led by the A.M.A. had already been organizing to make the field more exclusive. The report’s new professional requirements, developed with guidance from the A.M.A.’s education council, strengthened those efforts under the banner of improvement.

Elite White physicians now faced less competition from doctors offering lower prices or free care. They could exclude those they felt lowered the profession’s social status, including working-class or poor people, women, rural Southerners, immigrants and Black people.

And so emerged a vision of an ideal doctor: a wealthy White man from a Northern city. Control of the medical field was in the hands of these doctors, with professional and cultural mechanisms to limit others.

To a large degree, the Flexner standards continue to influence American medicine today.

The medical establishment didn’t follow all of the report’s recommendations, however.

The Flexner Report noted that preventing health problems in the broader community better served the public than the more profitable business of treating an individual patient.

“The overwhelming importance of preventive medicine, sanitation, and public health indicates that in modern life the medical profession” is not a business “to be exploited by individuals,” it said.

But in the century since, the A.M.A. and allied groups have mostly defended their member physicians’ interests, often opposing publicly funded programs that could harm their earnings.

Across the health system, the typically lower priority given to public health disproportionately affects Black Americans.

Lower reimbursement rates discourage doctors from accepting Medicaid patients. Twelve states, largely in the South, have not expanded Medicaid as part of the Affordable Care Act.

Specialists like plastic surgeons or orthopedists far out-earn pediatricians and family, public health and preventive doctors — those who deal with heart disease, diabetes, hypertension and other conditions that disproportionately kill Black people.

With Americans able to access varying levels of care based on what resources they have, Black doctors say many patients are still, in effect, segregated.

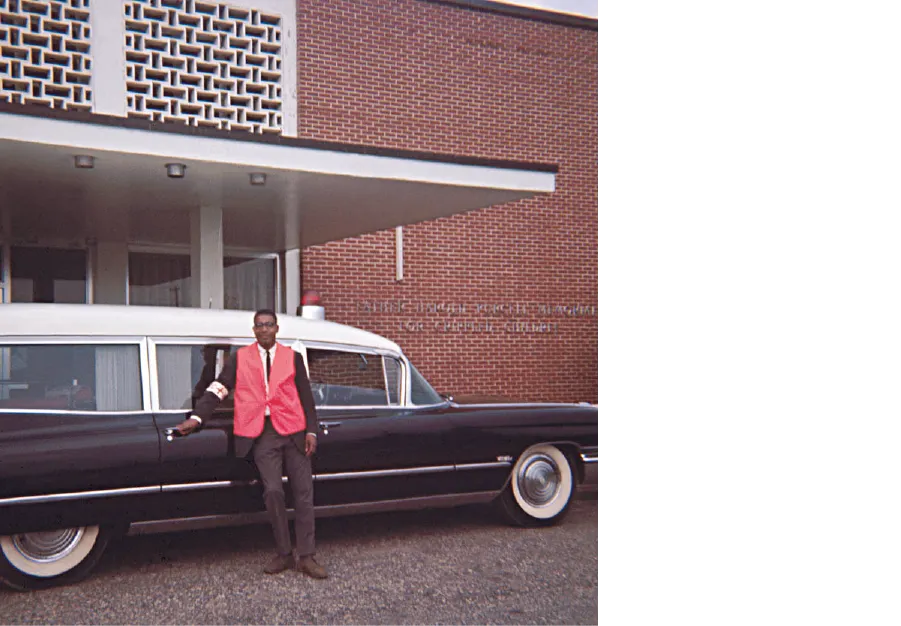

The trans-Atlantic slave trade began a tormented relationship with Western medicine and a health disadvantage for Black Americans that has never been corrected, first termed the “slave health deficit” by the doctor and medical historian Dr. W. Michael Byrd.

Dr. Byrd, born in 1943 in Galveston, Texas, grew up hearing about the pain of slavery from his great-grandmother, who was emancipated as a young girl. Slavery’s disastrous effects on Black health were clear. But by the time he became a medical student, those days were long past — why was he still seeing so many African Americans dying?

Dr. Linda A. Clayton had the same question.

Her grandfather had also been emancipated from slavery as a child. And growing up, she often saw Black people struggle with the health system — even those in her own family, who were well able to pay for care. Her aunt died in childbirth. Two siblings with polio couldn’t get equitable treatment. Her mother died young of cancer after being misdiagnosed.

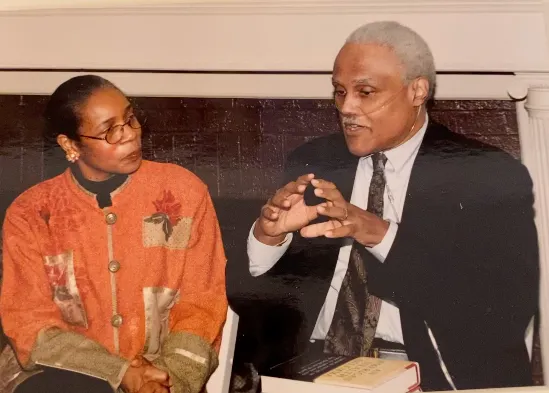

By 1988, when Dr. Byrd and Dr. Clayton met as faculty members of Meharry Medical College in Nashville, he had been collecting data, publishing and teaching physicians about Black health disparities for 20 years, calling attention to them in the news media and before Congress.

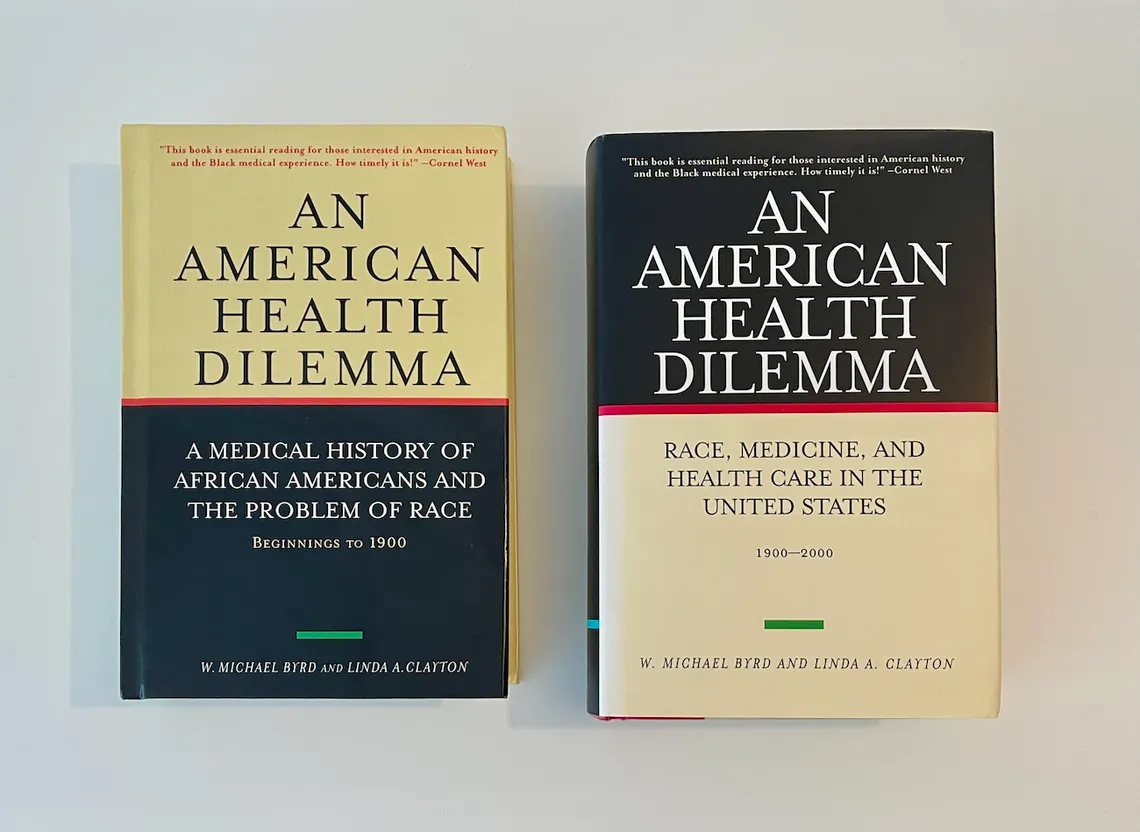

In their decades-long partnership and marriage that followed, the two built on that work, constructing a story of race and medicine in the U.S. that had never been comprehensively told, publishing their findings in a two-volume work An American Health Dilemma.

Much has changed since the publication of the Flexner Report.

Racial discrimination is prohibited by law. Medical schools, practices and hospitals are desegregated.

In 2008, a past A.M.A. president, Dr. Ronald M. Davis, formally apologized to Black doctors and patients. The association has established a minority affairs forum and a national Center for Health Equity; collaborated with the National Medical Association, historically Black medical schools and others in Black health; and created outreach and scholarships.

But Dr. Clayton and Dr. Byrd have questioned whether the field is working hard enough to change the persistent inequalities. And they aren’t the only experts wondering.

To Adam Biggs, an instructor of African American studies and U.S. history at the University of South Carolina Lancaster, Flexner’s figure of the elite physician still reigns. That person is most likely to have resources to shoulder the tuition and debt; to get time and coaching for testing and pre-medical preparation; and to ride out years of lower-paid training an M.D. requires.

Evan Hart, an assistant professor of history at Missouri Western State University, has taught courses on race and health. She said medical school tuition is prohibitively expensive for many Black students.

Earlier this year, an A.M.A. article estimated there are 30,000-35,000 fewer Black doctors because of the Flexner Report.

Today, Black people make up 13% of Americans, but 5% of physicians — up just two percentage points from half a century ago. In the higher-paying specialties, the gap grows. Doctors from less wealthy backgrounds and other disadvantaged groups are underrepresented, too.

This disparity appears to have real-world effects on patients. A study showed Black infant mortality reduced by half when a Black doctor provided treatment. Another showed that Black men, when seen by Black doctors, more often agreed to certain preventive measures. Data showed over 60% of Black medical school enrollees planned to practice in underserved communities, compared with less than 30% of Whites.

The limits of progress are perhaps clearest in the continuing numbers of Black Americans suffering poor health and early death. Millions remain chronically uninsured or underinsured.

According to Dr. Clayton, a key problem is that the health system continues to separate those with private insurance and those with public insurance, those with resources versus those without, the care of individuals versus the whole.

During the Civil Rights movement, Medicare and Medicaid passed in part because of the advocacy of Black doctors, extending care to millions of lower-income and older Americans. The A.M.A. opposed federal health insurance until the 1960s.

But the A.M.A.’s long battle against public programs has contributed to the U.S.’s position as the only advanced nation without universal coverage. When a social safety net is left frayed, research shows, it may hurt Black Americans more, and it also leaves less privileged members of all races exposed.

“It is basically a segregated system within a legally desegregated system,” Dr. Clayton said.

In February, Dr. Byrd passed away from heart failure in a hospital in Nashville at 77. Dr. Clayton was holding his hand.

Before his death, the two doctors had given hours of interviews to The New York Times/The Marshall Project over the course of six months.

Dr. Byrd said he wanted to spread awareness to more American doctors — and Americans generally — about the Black health crisis that slavery began, and that continues in a health system that hasn’t fully desegregated.

The doctors’ work showed that never in the country’s history has Black health come close to equality with that of Whites.

“We’re still waiting,” Dr. Byrd said.

An earlier version of this article imprecisely described the American Medical Association's stance over time toward federal health insurance in the Civil Rights movement. The A.M.A. opposed federal health insurance for much of the movement, into the 1960s. It did not oppose it for the entire era, supporting the final version of Medicaid that passed in 1965.