The epithet is a quarter-century old, but it still has sting: “He called them superpredators,” Donald Trump insisted in his final debate with Joe Biden. “He said that, he said it. Superpredators.”

“I never, ever said what he accused me of saying,” Biden protested. While there is no record of Biden using the phrase, much of the harsh anti-crime legislation embraced by both parties in the 1990s continues to be a hot-button issue to this day. From the moment the term was born, 25 years ago this month, “superpredator” had a game-changing potency, derived in part from the avalanche of media coverage that began almost immediately.

“It was a word that was constantly in my orbit,” said Steve Drizin, a Chicago lawyer who defended teenagers in the 1990s. “It had a profound effect on the way in which judges and prosecutors viewed my clients.”

An academic named John J. DiIulio Jr. coined the term for a November 1995 cover story in The Weekly Standard, a brand-new magazine of conservative political opinion that hit pay dirt with the provocative coverline, “The Coming of the Super-Predators.”

Then a young professor at Princeton University, DiIulio was extrapolating from a study of Philadelphia boys that calculated that 6 percent of them accounted for more than half the serious crimes committed by the whole cohort. He blamed these chronic offenders on “moral poverty … the poverty of being without loving, capable, responsible adults who teach you right from wrong.”

DiIulio warned that by the year 2000 an additional 30,000 young “murderers, rapists, and muggers” would be roaming America’s streets, sowing mayhem. “They place zero value on the lives of their victims, whom they reflexively dehumanize as just so much worthless ‘white trash,’" he wrote.

But who was doing the dehumanizing? Just a few years before, the news media had introduced the terms “wilding” and “wolf pack” to the national vocabulary, to describe five teenagers—four Black and one Hispanic—who were convicted and later exonerated of the rape of a woman in New York’s Central Park.

“This kind of animal imagery was already in the conversation,” said Kim Taylor-Thompson, a law professor at New York University. “The superpredator language began a process of allowing us to suspend our feelings of empathy towards young people of color.”

The “superpredator” theory, besides being a racist trope, was not borne out in crime statistics. Juvenile arrests for murder—and juvenile crime generally—had already started falling when DiIulio’s article was published. By 2000, when tens of thousands more children were supposed to be out there mugging and killing, juvenile murder arrests had fallen by two-thirds.

It failed as a theory, but as fodder for editorials, columns and magazine features, the term “superpredator” was a tragic success—with an enormous, and lasting, human toll.

Terrance Lewis was 19 and returning from work in 1997 when Philadelphia police trapped him on a bridge, guns drawn, and arrested him for a murder that he spent 21 years in prison trying to prove he did not commit. Only last year did the judge finally throw out his homicide conviction, citing faulty eyewitness testimony.

“I’m a recipient of the backlash of that superpredator rhetoric,” said Lewis, now 42. “The media believed in the rhetoric. All the coverage from back in that era was to amplify that rhetoric.”

DiIulio’s big idea wasn’t original. His mentor as a graduate student at Harvard, the influential political scientist James Q. Wilson, had been warning for years about a new breed of conscience-less teen killers. (“I didn’t go to Harvard,” DiIulio told one interviewer. “I went to Wilson.”)

But DiIulio was a clever popularizer who quickly became a darling of the think-tank circuit—and of the media. The Marshall Project’s review of 40 major news outlets in the five years after his Weekly Standard article shows the neologism popping up nearly 300 times, and that is an undercount.

There was the Philadelphia Inquirer’s fawning magazine profile of DiIulio, who grew up there. (Until recently, Pennsylvania had the country’s largest population of people still serving life sentences without parole—for crimes they committed as children.) There was also a lengthy, mostly gentle New Yorker profile; a spot on The New York Times’ op-ed page; and an appearance on the CBS Evening News.

The media exposure led to conference invitations, which led to more media exposure. The word “superpredator” became so much a part of the national vocabulary that journalists and talk show hosts used it without reference to DiIulio—including even Oprah Winfrey, in a segment on “Good Morning America.”

The Weekly Standard’s founding editor, Bill Kristol, now downplays the blockbuster cover story of his defunct magazine. But he admits: “It struck a nerve. And it caught on.”

The notion of an impending wave of teenage savagery caught on among criminologists, too.

“How did these ideas get supported and weaponized throughout the decades? Academics also played a role,” says Jeremy Travis, then at the National Institute of Justice, the research arm of the Justice Department, and now at Arnold Ventures, a charitable foundation from which The Marshall Project receives funding.

James Alan Fox, a professor of criminology at Northeastern University, says he never used the term “superpredator,” but he warned in numerous media appearances about the coming teen crime wave, and makes no apologies. “One of the things about forecasts is that they’re sometimes wrong,” he said.

Meanwhile, having sparked the media’s feeding frenzy, DiIulio soon started sounding doubtful. “The term ‘superpredator’ has become, I guess, part of the lexicon,” he told NPR in the summer of 1996. The word had “sort of gotten out and gotten away from me.”

Of the 281 media mentions of “superpredators” we found from 1995 to 2000, more than three in five used the term without questioning its validity. The remainder included writers who contested DiIulio’s thesis in op-ed articles of their own, readers writing outraged letters, or journalists quoting a number of dissenters in their articles.

Although it made the news pages, the term “superpredator” appeared most often in commentaries and editorials, and in newsmagazines. An emerging “journalism of ideas” would gather force through the 1990s as cable television and the internet took hold. News outlets that once focused on telling their readers the basic facts now felt they had to explain, in the words of one of Newsweek’s advertising slogans, “Why it happened. What it means.”

In January 1996, the magazine asked in a headline, “‘Superpredators’ Arrive: Should we cage the new breed of vicious kids?” (Full disclosure: We both worked at Newsweek in the 1990s, and regret not protesting its crime coverage at the time.)

TRACKING MENTIONS

OF “SUPERPREDATOR”

The term “superpredator” first appeared in a cover story in The Weekly Standard, a new conservative magazine based in Washington. The author, a young academic named John DiIulio, Jr., warned of a coming wave of remorseless teen killers. The theory spread quickly through the media.

The Chicago Tribune devoted its entire op-ed page to reprinting the article that had coined the term “superpredator” in the Weekly Standard. The notion of “superpredators” appeared early and often in editorials and columns in the Chicago Tribune.

Newsweek was the first major media outlet to jump on the “superpredator” theory, but not the last. All three of the major national newsmagazines ran big “superpredator” stories in 1996, reaching millions of readers. The authors worked at Newsweek at the time.

Presidential candidate Bob Dole warned on the campaign trail that “today’s newborns will become tomorrow’s super-predators.” The Associated Press article was picked up widely by newspapers, including the Los Angeles Times, which frequently mentioned the term.

Syndicated columnists who wrote about “superpredators” were often picked up in local newspapers. The “ticking time bomb” metaphor was widely used.

Sometimes the term appeared in opinion columns addressing other subjects, with "superpredator" mentioned only in passing. But this, too, helped cement the term in the national lexicon.

By the end of the decade, the sharp decline in juvenile crime could no longer be ignored. Many newspapers began running stories about how “superpredators” had failed to appear – including the Chicago Tribune, which had earlier championed the theory.

It’s commonplace to blame local news media for exaggerated crime fears, especially local TV with its famous dictum, “if it bleeds, it leads.” But crime coverage went national in the 1990s. According to one study, at the beginning of the decade, the three national news networks ran fewer than 100 crime stories a year on their nightly news broadcasts. By the end of the ’90s, they were running more than 500. On NBC News, a February 1993 segment on “Nightly News” focused on teen killers in the suburbs and rural areas, while one in December 1994 warned of a crime wave as America’s teen population swelled.

The record doesn’t show then-President Bill Clinton using the word “superpredator,” but Hillary Clinton did as first lady. And he certainly helped amplify crime as a national story. Political reporters were dazzled by his legerdemain in stealing a traditionally Republican issue, promising more law enforcement on the streets and tougher penalties for juvenile offenders.

The 1994 Crime Bill, a package of mostly draconian federal laws, was national news. And Sen. Robert Dole, the Kansas Republican running against Clinton in 1996, with the economy humming and the Cold War over, needed an issue to hammer. When he talked about “superpredators,” that made national news, too.

As some criminologists explained at the time, what drove juvenile homicides in the 1990s wasn’t a new breed of violent teens. It was probably the greater availability of guns, making fights and gang rivalries among kids more lethal than before, said Franklin Zimring, a Berkeley law school professor. But to paraphrase Mark Twain, the truth was still putting on its shoes while the “superpredators” ran out the door.

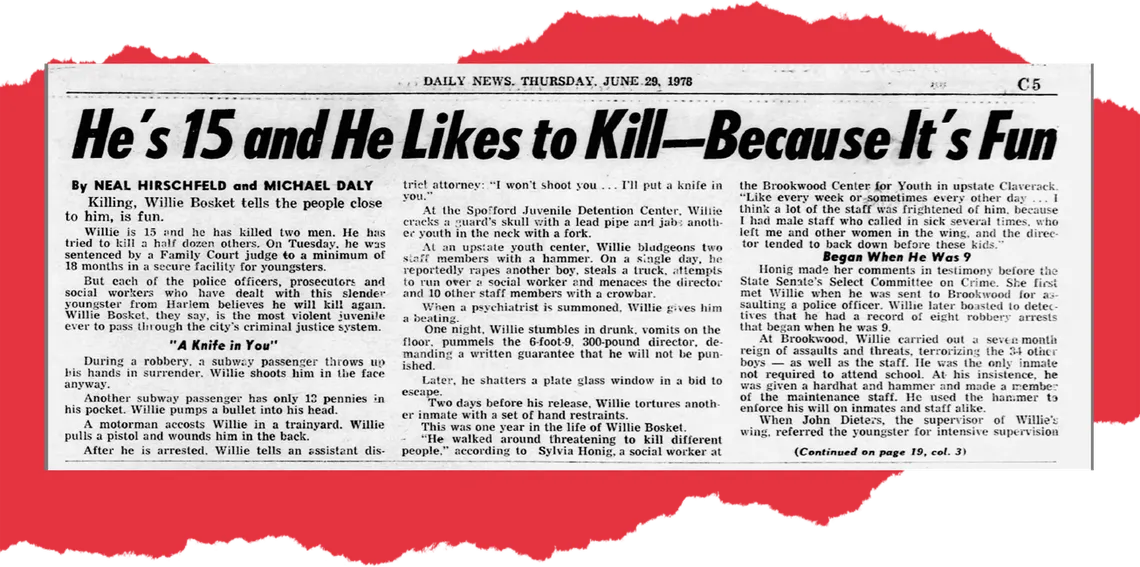

State legislatures were already busy dismantling a century’s worth of protections for juveniles when the fear of “superpredators” gave them a new push. New York had started the trend in 1978 after 15-year-old Willie Bosket killed two people on the subway. The media led that charge, too: Gov. Hugh Carey read a sensationalized story about Bosket in the New York Daily News (“He’s 15 and He Likes to Kill—Because It’s Fun”), and immediately called a special session of the legislature that stripped children of many protections of juvenile court.

Illinois followed suit, starting in 1982. At the end of Denver’s media-driven “summer of violence” panic in 1993, Gov. Roy Romer pushed through an “iron-fist” overhaul of Colorado’s juvenile justice system. By the end of the 1990s, virtually every state had toughened its laws on juveniles: sending them more readily into adult prisons; gutting and sidelining family courts; and imposing mandatory sentences, including life sentences without parole.

Readers who had already been subjected to a steady stream of horrific stories about child killers were primed for the “superpredator” theory. In Chicago, gruesome murders by children rocked the city in the early 1990s, including the case of Robert Sandifer, an 11-year-old whose love for cookies earned him the nickname “Yummy.” He was being sought for the murder of a 14-year-old girl in late summer 1994, when he was himself murdered by brothers Cragg and Derrick Hardaway, ages 16 and 14.

The local crime became a national story. Time magazine put Yummy’s picture on the cover: “So Young To Kill. So Young To Die.” By the time Derrick Hardaway was sentenced in adult court in 1996, at the height of the “superpredator” frenzy, he got 45 years in prison for Yummy’s murder. Not for pulling the trigger, but for driving his brother’s getaway car.

“I hate the media,” said Hardaway, who was released in 2016, in an interview last month. “I feel like I was convicted through the media.”

“The reaction was, the way to stop this crime problem is to hit ‘em hard,” said Don Wycliff, then the editor of the Chicago Tribune editorial pages. “I don’t recall a lot of persuasive dissenting voices at that time.”

When the “superpredator” concept was born a year after Yummy’s death, the Trib was all in. Just 10 days after DiIulio’s piece, the editorial board cited him in its argument for bringing back orphanages. A prominent and widely syndicated columnist for the Tribune, Bob Greene, advised readers to “stop thinking of the superpredators as merely some projected future phenomenon [but] something based on current fact.” The Tribune even devoted its entire op-ed page to reprinting DiIulio’s Weekly Standard piece.

“What can I say?” Wycliff said. “It seemed to explain a lot of things.”

The Chicago Tribune would later publish exceptional work uncovering years of police abuse and misconduct by local prosecutors. But reporter Maurice Possley said his sources sometimes asked, “Where was the Tribune when all this bad stuff was going on in these courtrooms?”

Journalists of color say that a lack of diversity in American newsrooms influenced criminal justice coverage. Black reporters at the Tribune were so dismayed by their White editors’ narrow outlook that in the early 1990s, one of them, Dahleen Glanton, organized a minivan ride to the city’s Black neighborhoods.

“There were top editors who had never been to the South Side of Chicago,” she remembers. (The editors most directly responsible for the Chicago Tribune’s op-ed page when it reprinted DiIulio’s piece, Wycliff and Marcia Lythcott, are both Black. Neither one remembers making the decision to run it. “I hated that term,” Lythcott says now.)

By the late 1990s, the “superpredator” mania was dying down. “Young killers remain well-publicized rarity,” a Tribune headline said in February 1998. “‘Superpredators’ fail to grow into forecast proportions.”

In 2001, DiIulio admitted his theory had been mistaken, saying ''I'm sorry for any unintended consequences.” In 2012, he even signed on to a brief filed with the U.S. Supreme Court supporting a successful effort to limit life sentences without parole for juveniles. (DiIulio’s wife said he was not available for comment for this article due to ill health.)

As the Biden-Trump debates showed, politicians now feel the need to backpedal from the term. When she was running for president in 2016, Hillary Clinton was pressed to apologize for using “superpredators” 20 years before.

Few media outlets have apologized for “superpredators.” The Los Angeles Times conceded in September that “an insidious problem ... has marred the work of the Los Angeles Times for much of its history … a blind spot, at worst an outright hostility, for the city’s nonwhite population.” Indeed, our analysis shows that the L.A. Times used “superpredator” more than any other major newspaper. But it was hardly alone in branding a generation of young men of color as animals and paving the way for harsher juvenile justice.

“If we don’t acknowledge the impact of what past stories did," said law professor Taylor-Thompson, "I’m not sure the media’s behavior will change.”

Carroll Bogert is president of The Marshall Project. LynNell Hancock is professor emerita at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

Additional research was provided by Kio Herrera and Noya Kohavi, and was sponsored by a grant from the Brown Institute for Media Innovation.

Source: Non-scientific review of all mentions of "superpredator" and its variations in 40 major U.S. news outlets from 1995 to 2000.