The Supreme Court today upheld Oklahoma’s contested death penalty protocol. At issue was the sedative midazolam, which Oklahoma, following several other states, uses first in a series of three drugs to execute inmates. The death row prisoners who brought the case argued that midazolam might not render them sufficiently unconscious for long enough, such that the paralytic agent that follows would cause an excruciating death by suffocation. Justice Alito, writing for the majority, said “the Constitution does not require the avoidance of all risk of pain. After all, while most humans wish to die a painless death, many do not have that good fortune.”

Because midazolam has never been tested for the purposes of execution — and, in a medical setting, is never used at the doses that Oklahoma uses — physicians have little evidence of whether it’s safe or effective. In the medical world, argued one doctor at a deposition in this case, the burden is on a drug company to prove that its drug is safe; without evidence, the assumption is that it’s not safe. But this doctor “confused the standard imposed on a drug manufacturer seeking approval of a therapeutic drug with the standard that must be borne by a party challenging a State’s lethal injection protocol,” Alito wrote. “Here, petitioners’ own experts effectively conceded that they lacked evidence to prove their case beyond dispute.”

Oklahoma had halted executions pending the outcome of this case, but the Court’s ruling clears the way for lethal injections to begin again. Now that midazolam has the Supreme Court’s blessing, the question is whether the state will be able to acquire any — pharmaceutical companies, at the urging of activists, have been shutting down traditional avenues to many drugs used in executions, including midazolam (a fact Alito notes with seeming annoyance).

Still, “midazolam remains a risky drug for states to use,” says Richard Dieter of the Death Penalty Information Center. “It’s one thing to say petitioners haven’t proven it’s going to be severely painful, and another thing for the state to take a chance with a drug that failed numerous times last year. The biggest risk is that midazolam fails to put the inmate into unconsciousness and therefore the execution is a spectacle, it horrifies people — it threatens the whole death penalty.”

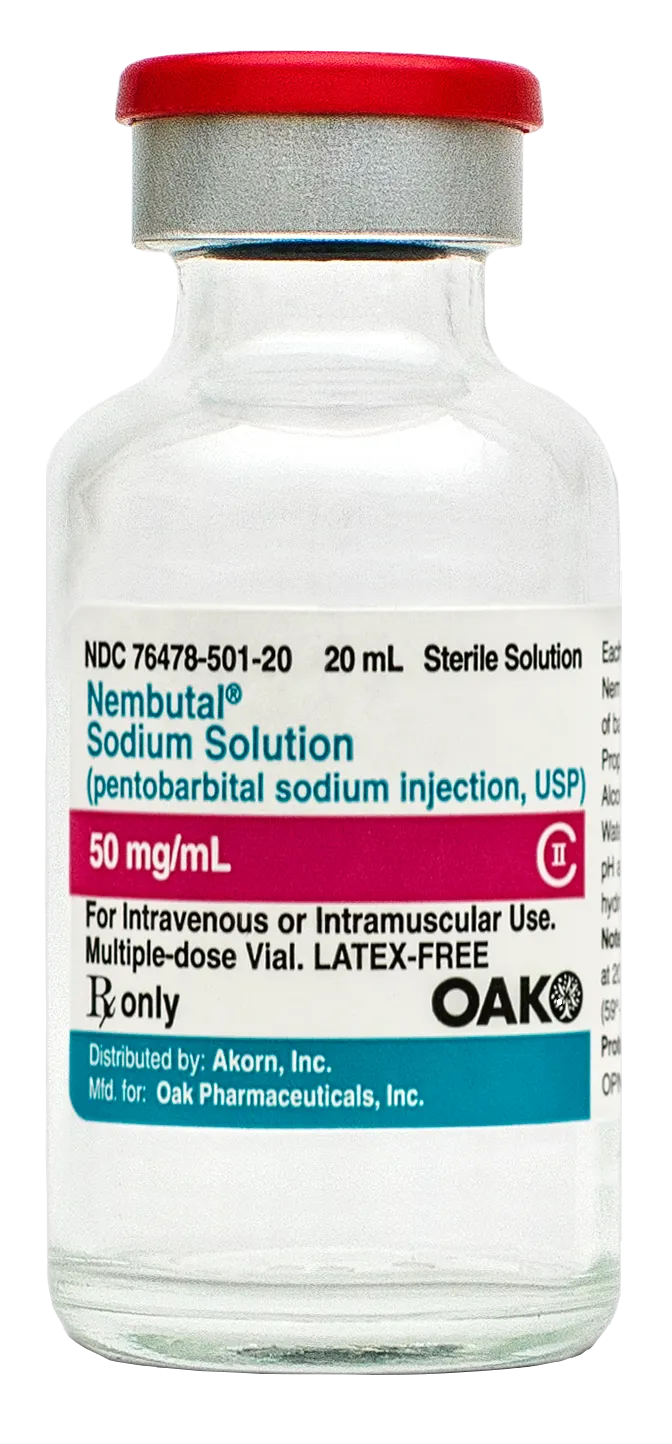

The Illinois-based generics manufacturer Akorn Pharmaceuticals announced this week it was restricting the sales of two of its drugs, midazolam and pentobarbital, to keep them out of execution chambers. In doing so, it joined a list of at least a dozen drug companies who have come out strongly against their products being used in capital punishment. A worldwide shortage of the lethal injection drug sodium thiopental has forced corrections departments around the country to try new drugs in new combinations, and as they do, the pharmaceutical industry has been on the defensive, shutting down avenues to these newly repurposed drugs almost as quickly as they’re announced. Many of these companies are European, but a growing handful are, like Illinois-based Akorn, in the United States.

Clear, unambiguous opposition to capital punishment is an obvious stance for companies in Europe, where the death penalty has been outlawed since the 1950s and is widely seen as a violation of human rights. But U.S. companies operate in murkier territory. The death penalty is legal in 32 states (notwithstanding several moratoriums) and supported by the majority of Americans. So companies’ objections to their drugs being used for executions do not focus on the death penalty itself, but rather on the FDA-approved uses of their products, their fear of legal liability, and image management.

After Indiana announced last year that it planned to use the surgical anesthetic, Brevital, in lethal injections, New Jersey-based Par Pharmaceuticals amended its contracts with all of its wholesalers, prohibiting them from selling Brevital to prisons — or to any other wholesaler or distributor that might do so in turn. “It’s not because we take public policy positions on issues like capital punishment,” Stephen Mock, a spokesman for the company, told The Marshall Project. Rather, “we’re a pharmaceutical company, and we have a mission statement. Par’s mission is to help improve the quality of life. Indiana’s proposed use of our product is contrary to our mission.”

Similarly, Dewey Steadman, a spokesperson for Akorn, told The Marshall Project, “The use of our products in executions goes counter to our philosophy of helping patients,” but added that “there’s other avenues to execute convicted inmates, and we respect the will of the people and the rule of law in those states.”

Akorn made this week’s announcement after inadvertently discovering, through court documents brought to light by the Anniston Star, that the Alabama Department of Corrections planned to use its midazolam for lethal injections. (Midazolam is a sedative used to reduce anxiety before a variety of surgical procedures; the drug is at the center of a Supreme Court case this term testing the constitutionality of these new drug combinations.) “The employees of Akorn are committed to furthering human health and wellness,” the company said in a statement. “In the interest of promoting these values, Akorn strongly objects to the use of its products to conduct or support capital punishment through lethal injection or other means.”

In addition to amending its contracts with wholesalers, Akorn also sent letters this week to attorneys general in all death penalty states, warning, “The use of midazolam and/or hydromorphone for lethal injection is clearly contradictory to the FDA approved indications for both products and — as controlled substances — the procurement or use of these products for executions may be in violation of the Controlled Substances Act.” The company asked any prisons that may have already purchased its medications for use in lethal injections to “immediately return our products for a full refund.”

This week, Georgia’s lethal injection drugs were in the headlines after the state postponed two executions, saying its vials of pentobarbital were “cloudy.” Georgia’s protocol uses only that one drug, whose FDA-approved uses include managing severe seizures and inducing a medically-managed coma for patients with brain injury. But the drug’s only manufacturer, the Danish company Lundbeck, announced in 2011 that it was implementing a restricted distribution program that would prevent the drug from being sold to prisons. “Lundbeck adamantly opposes the distressing misuse of our product in capital punishment,” the company said.

Like several other states, Georgia then turned to loosely-regulated compounding pharmacies to produce pentobarbital. But the identity of the pharmacy, the qualifications of the pharmacist, and other basic information about the drug’s origin remain unknown, thanks to a 2013 law that classifies such information as a “confidential state secret.”

This dance — manufacturers shut down a legitimate channel, corrections departments find another, shadier one — began in 2009 when the Illinois-based Hospira ceased production of sodium thiopental, the first drug in the traditional “three drug cocktail.” Facing manufacturing problems in its U.S. facilities, the company had planned to move production of the drug to Italy, but Italian authorities warned them they would be liable under EU law if the drug was ultimately used for executions. “Exposing our employees or facilities to liability is not a risk we are prepared to take,” the company said in 2011.

Indeed, Hospira was sued last year by the family of Ohio inmate Dennis McGuire, whose protracted execution left him gasping and writhing for more than 20 minutes. Hospira’s midazolam and hydromorphone were used in that execution. The company has put distribution controls in place for those drugs, but given “gray market” resales and the year-plus shelf life of drugs obtained before the controls were put in place, “Hospira cannot guarantee that a U.S. prison could not secure restricted products through other channels not under Hospira’s control,” the company said in a statement.

The labyrinthine U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain involves dozens of wholesalers and thousands of retailers, and a typical drug can change hands several times before it arrives at its destination. However, over the last decades, drug companies have become adept at putting controls on drug distribution in response to concerns about contamination, counterfeiting, and safety (a drug that can cause birth defects, for example, must have controls to prevent it from being taken by pregnant women). Human rights groups like the UK-based Reprieve have encouraged companies to use these same types of distribution controls to keep their drugs out of death chambers. In the simplest and most common scheme, drug manufacturers sell only to a group of “trusted” wholesalers who promise not to sell designated products to prisons or to other wholesalers.

In the months prior to Akorn’s name appearing in court documents in Alabama, a shareholder resolution called on the company to put stricter controls on distribution of its midazolam product. Authored by the New York state Common Retirement Fund, which owns $14.5 million worth of Akorn stock, the resolution warns that by not putting stricter controls in place, Akorn “has been exposed to reputational risk, and jeopardizes its role and reputation as a provider of health oriented products. There is also the possibility of increased financial and legal risk to the company resulting from the actual use of its products in executions.”

New York state Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, who manages the Common Retirement Fund, says he has filed a similar shareholder request with another generics manufacturer, the Pennsylvania-based Mylan Pharmaceuticals.