Just before sunrise on a spring morning last year, Larry Maples shot and killed his wife, Heather. He had tracked her to the home of a former boyfriend, a ranch hand named Moses Clemente. Maples shot and wounded him. He then called 911, handed his Colt .45 revolver over to the sheriff’s deputies and confessed.

It was a shocking event for Van Zandt County, a largely agricultural swath of East Texas with roughly 50,000 residents. The local authorities had never sent someone to death row, but Maples — by shooting Clemente along with his wife and thereby aggravating the murder — qualified for the death penalty under state law. It was up to the young district attorney, Chris Martin, to decide whether to seek that punishment.

Martin had been telling reporters he might seek the death penalty, but behind closed doors with the victim’s family and Clemente, the D.A. now said he wasn’t sure the case was strong enough to convince a jury that Maples should be executed.

“He said, ‘If we go with the death penalty, Maples will get more attorneys,’” Lori Simpson, Heather’s sister, recalled. “There will be more witnesses, expert testimony, and then he will get an automatic appeal. That could cost millions of dollars, and your family doesn't want to go through those appeals, and we don't want to spend the money on that if we're not able to get capital punishment.’”

Martin’s concerns about the public expense of a death-penalty prosecution, which Clemente confirmed, were remarkable only for the bluntness with which Martin expressed them. While many prosecutors are still reluctant to admit that finances play a role in their decisions about the death penalty, some of them – especially in small, rural counties – have been increasingly frank in wondering whether capital punishment is worth the price to their communities. “You have to be very responsible in selecting where you want to spend your money,” said Stephen Taylor, a prosecutor in Liberty County, Texas. “You never know how long a case is going to take.”

Some prosecutors are far more blunt, and even hyperbolic, as they lament the state of affairs. “I know now that if I file a capital murder case and don't seek the death penalty, the expense is much less,” said James Farren, the District Attorney of Randall County in the Texas panhandle. “While I know that justice is not for sale, if I bankrupt the county, and we simply don't have any money, and the next day someone goes into a daycare and guns down five kids, what do I say? Sorry?”

Since capital punishment was reinstated by the Supreme Court in 1976, the cost of carrying out a death penalty trial has risen steadily. Increasing legal protections for defendants have translated into more and more hours of preparatory work by both sides. Fees for court-appointed attorneys and expert witnesses have climbed. Where once psychiatrists considered an IQ test and a quick interview sufficient to establish the mental state of a defendant, now it is routine to obtain an entire mental health history. Lab tests have become more numerous and elaborate. Defense teams now routinely employ mitigation experts, who comb through a defendant’s life history for evidence that might sway a jury towards leniency at the sentencing phase. Capital defendants are automatically entitled to appeals, which often last for years. Throughout those years, the defendant lives on death row, which tends to cost more due to heightened security.

In states such as Texas, Arizona, and Washington, where county governments pay for both the prosecution and defense of capital defendants (nearly all of whom are indigent) when they go to trial, the pressure on local budgets is especially strong. To ease the fiscal burden, some states have formed agencies to handle the defense or prosecution of capital cases. Other states reimburse counties for the expenses of a trial.

But even with that help, county officials around the country have sometimes had to raise taxes and cut spending to pay for death penalty trials. District attorneys have taken note. Many remain reluctant to acknowledge how fiscal concerns affect their decisions — they don’t want to appear to be cheapening the lives of murder victims. But a few are surprisingly candid. Their statements suggest that money is more than ever part of the explanation for the steep decline in death-penalty cases over the past decade. That is particularly the case in Texas, where there are few political obstacles to carrying out executions.

In the six states that have abolished capital punishment over the past decade, Republican and Democratic officials have also emphasized the cost of the death penalty as a major rationale. Even in states that retain the punishment, cost has played a central role in the conversion narratives of conservative lawmakers, public officials, and others who question the death penalty as a waste of taxpayer dollars.

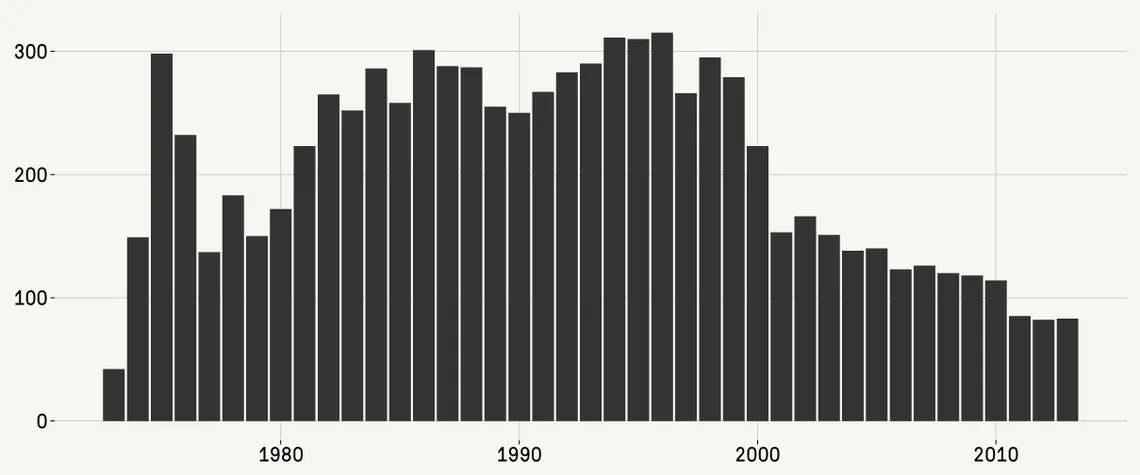

The rising cost of capital trials disproportionately affects counties with small populations. While the number of death sentences in the United States has been dropping steadily since a peak in the mid-1990s, an overwhelming number of the cases still being filed come from urban counties. There, the tax bases are larger, and the impact of an expensive trial may be more easily absorbed. (Harris County, where Houston is located, has been responsible for more executions than Georgia and Alabama combined.) Texas counties with fewer than 300,000 residents sought the death penalty on average 15 times per year from 1992 to 1996. Between 2002 and 2005, the average was four.

Prosecutors don’t cite statistics when discussing the costs of the death penalty; they tell stories. In Texas, they point to Jasper County, near the Louisiana border, where in June 1998 three white supremacists killed a black man, James Byrd Jr., by chaining his ankles to the back of their pickup truck and dragging his body for more than three miles. The murder made international headlines and led to new state and federal hate crime legislation.

But among Texas prosecutors, the case took on another meaning as well. They noticed how Jasper County struggled to pay for the trials, in which two of the men were sentenced to death. Administrators doled out a total of $730,640.55 for the prosecution, defense, and various court costs. The local tax rate had been increasing by less than 5 percent per year, but in 1999 and 2000, the two years the county prepared for the trials, the tax rate increase was bumped to 8 percent. The county auditor at the time told the Wall Street Journal that the last comparable budget shock was a flood in the 1970s, which had “wiped out roads and bridges.”

The officials who manage local budgets mostly stay out of the district attorneys’ decisions, but on occasion they have urged district attorneys to avoid seeking the death penalty. “It's safe to say they hope they don't ever get” a death penalty case, said Lonnie Hunt, an official with the Texas Association of Counties and a former judge. “It's like anything else — the people in charge of managing the money of the county hope there isn't a wildfire or a tornado.”

After the Jasper case, county officials from around Texas went to the capitol to beg for help, and Texas lawmakers approved a grant program for death penalty cases, a mechanism that is also used in Indiana, Ohio, and Washington. States have tried to ease the burden on local counties for death penalty cases in other ways as well, including trial assistance from attorneys general and the creation of statewide public defender offices.

That outside help has only had a limited effect. Since 2002, the Texas Governor’s Office has awarded just over $2 million to counties throughout Texas for capital trials, but stretched out over 12 years and spread across 22 counties, the grants have made a small dent. In 2008, Gray County, in the Texas panhandle, received $131,009.95 from the state as it sought the death penalty against Levi King for the murder of a father, a pregnant mother, and their teenage son. Still, the county paid $885,382.33 for the trial, and was forced to raise taxes and suspend annual raises for county employees.

In 2005, partly to stem the tide of expensive death penalty cases, Texas became the last state in the country to establish a sentence of life without the possibility of parole. Now, juries could return a life sentence and know, as one prosecutor put it, that defendants “are never, never, never going to come out except in a box.”

Levi King benefited from this shift. After a day of deliberation, a single juror refused to give him a death sentence. He was already serving a life sentence for two other murders he had committed in Missouri. So, after a million-dollar trial, his fate was unchanged.

The King case was another cautionary tale for prosecutors. District attorneys “used to be confident about spending the money,” explained defense attorney David Dow, who runs a death penalty clinic at the University of Houston Law Center. “Now, because so often juries bring back a life sentence, it makes the downside of spending all that money all the clearer, because if you don’t get a death sentence you've wasted the money.”

The prosecutor for Mohave County, Arizona, Greg McPhillips, had no doubt that James Vandergriff deserved to be sentenced to death. In 2010, Vandergriff was charged, along with his girlfriend, with murdering their 5 week-old son, Matthew. The autopsy showed broken bones, bruises, and signs the victim had been shaken.

Murders are rare in Mohave County, a corner of northwestern Arizona where 200,000 residents are spread over 13,000 square miles of desert. McPhillips, who has been county attorney for nearly two decades, seldom has more than one pending death penalty case at a time, and each takes roughly three years to bring to trial. He allowed Vandergriff’s girlfriend to plead to a 15-year sentence for failing to protect the baby. But for Vandergriff, he felt the case was a clear-cut example of the kind of heinous crime that his constituents would agree should lead to an execution.

But then McPhillips realized how expensive the trial would become. Shaken baby cases are forensically complex. The prosecution and defense end up paying doctors with differing opinions to debate the true nature of the baby’s death in front of a jury. “If you talk to two medically respected doctors, they disagree on this stuff,” McPhillips explained.

McPhillips also knew his county had another death penalty trial already in the works, that of a man who had stabbed an 18 year-old girl to death during a burglary. In that case, there had been eyewitnesses. Nobody had directly seen the death of Vandergriff’s baby. The case also came at a bad financial moment. In the wake of the nationwide economic downturn, Mohave County had seen $1.3 million in tax revenue unexpectedly diverted to the state.

After a series of hearings, McPhillips filed a motion stating he would not seek the death penalty, framing his decision as a matter of public service to taxpayers. “The County Attorney’s Office wants to do their part in helping the County meet its fiscal responsibilities in this time of economic crisis not only in our County but across the nation,” he wrote.

“I don't want to waste the county's money, as much as it galls me that justice is defined by how much money we have,” McPhillips said in an interview. He allowed Vandergriff to plead guilty for a sentence of 20 years. While the sentence may not have been harsh enough for some constituents, McPhillips did not face backlash from voters. Four years later, he does not regret his decision, but he is still bitter that money played any role at all. “I have to admit this is sort of a sore spot,” he said. “I think every prosecutor believes there shouldn't be a price on justice, but we've made it have a price, and I think that's been a tactic of the defense bar.”

Many prosecutors are quick to blame defense lawyers for driving up the cost of death penalty cases. Defense attorneys argue back that a robust, expensive defense is necessary to ensure that defendants get a fair trial. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t also a tactic, designed, in the words of one prosecutor, “to soften us up.” Houston lawyer Katherine Scardino is considered by her colleagues to be one of the best defense attorneys in the state. (One calls her “the Clarence Darrow of death penalty lawyers in Texas.”) She is a mainstay of training seminars, where she gives other defenders simple instructions for what to do when appointed in a death penalty case. “Spend money,” she says with a bright east Texas twang. “That will get everybody’s attention.”

In some states, including Washington and California, the district attorneys’ decision is even more fraught because they have no assurance an execution will ever be carried out.

In Cañon City, Colorado, this September Jaacob Van Winkle pled guilty and accepted a life sentence for murdering his ex-girlfriend and her two children, ages 5 and 9, and raping her teenage daughter. District Attorney Thom LeDoux talked with district attorneys around the state and determined not only that the case would cost roughly $2 million over three to five years, but also that he could not be sure the case would actually result in an execution. Earlier this year, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper issued a “temporary reprieve” to Nathan Dunlap, who was facing execution for the 1993 murder of four people. The governor called the overall death penalty system in his state “imperfect and inherently inequitable.” Unsure whether Hickenlooper would allow any execution to take place under his tenure, LeDoux found it difficult to justify spending so much money.

At a plea hearing in June, some of the victim’s family members disagreed over whether the life sentence was a just result. “I feel like if he was 300 miles south in Texas, we would be on an escalator to death row, and I think that's appropriate," the victim’s brother Danny Stotler told reporters outside the courtroom after the hearing. “Mr. LeDoux properly thought he should be put to death. Unfortunately the system that a liberal government has established has made it so hard for the state of Colorado to pursue [a death sentence] that they’ve eliminated the death penalty without eliminating the death penalty.”

LeDoux said cost was one of “many factors” he analyzed as he confronted his state’s political ambivalence. It was the second time his office had considered and then declined to seek the death penalty for an aggravated murder. When asked — politics aside — whether a murder might come along that is heinous to enough to overcome the budget issue, he said, “The two we looked at were really aggravated, so I guess the answer is no, I don't know what it'd look like.”

Texas does not suffer from political ambivalence, and certain cases are considered non-negotiable when it comes to the death penalty, including murders of law enforcement officers. The advent of life without parole allowed district attorneys in rural counties to save money by giving them a harsh alternative, but the remaining death penalty cases were still straining their county budgets. In 2007, Nacogdoches County District Attorney Stephanie Stephens wrote to her colleagues in the online forum of the Texas District and County Attorneys Association, asking for information on how much a death penalty trial might cost. “I cannot put my head in the sand and pretend like this isn't going to be a significant expense to my county,” she wrote.

That year, a group of judges and attorneys from small counties in northwest Texas hatched a plan to ease the burden. Counties, they decided, would pay into a pool to create a single public defender office for death penalty cases. The idea appealed to prosecutors because better defense work would mean that death sentences would not be as likely to get reversed on appeal.

Seven years later, the Regional Public Defender Office, based in Lubbock, is funded with state grants and fees from participating counties, which cover about two thirds of the state. Other states have capital defense offices, and Utah has experimented with creating an insurance system among counties, but the Texas model — in which counties pool their money to run a defender office exclusively for death penalty cases — is unique. Some tiny counties that have never had a death penalty case pay only $1,000 a year to participate. “Most counties, statistically, will not get a capital case,” said Jack Stoffregen, the office’s director and a longtime defense attorney. “It's kind of like a risk pool.”

As the office began taking cases, some defense attorneys worried that better representation would provide an incentive for prosecutors to seek the death penalty more often, since cost would no longer be as much of an impediment.

Those worries proved unfounded. Last year, the Public Policy Research Institute at Texas A&M University released a report, which found that in counties working with the death-penalty defense office, prosecutors were actually less likely to seek the death penalty.

This was because attorneys from the defense office pour most of their funds into mitigation investigations, in which specialists find out everything they can about a defendant’s past so they can present a better explanation for the crime to a jury, hoping to sway jurors toward a life sentence. With a history of abuse or a traumatic brain injury, defense lawyers are better prepared to bargain with prosecutors for a plea deal. “Mitigation specialists are specifically responsible for uncovering information and developing a narrative about the client capable of convincing a jury that death is not an appropriate penalty,” the report states. “The same evidence can often persuade a prosecutor that a plea agreement is in the best interest of the state.”

Part of that “best interest” is the money that will be saved by avoiding the death penalty. To date, the Regional Public Defender Office has handled more than 70 cases. Only five have gone to trial.

There is every reason to believe that even as Texas retains its reputation as the state most willing to impose the death penalty, the number of actual death sentences will continue to drift downward year by year, remaining only an option for urban counties who can pay for it. Many prosecutors see this as a victory for death penalty opponents over public opinion, which still favors the punishment. “We're never going to get the majority of the public to give up the death penalty,” said Farren, the D.A. in Randall County, so defense attorneys will “make it so expensive and such a waste that we'll get through the back door what we couldn't get through the front door.” On the other hand, if capital punishment does eventually disappear, it may be cold comfort to those opponents to know that Americans surrendered it not because of moral opprobrium, but as a matter of simple thrift.