New York’s Department of Corrections last week released a report that generated triumphant headlines in some of the upstate communities that house prisons: “Recidivism rates for ex-inmates reach 28-year low,” “Fewer Offenders Going Back to Prison,” and “New York Sees Less Crime by Ex-Offenders.”

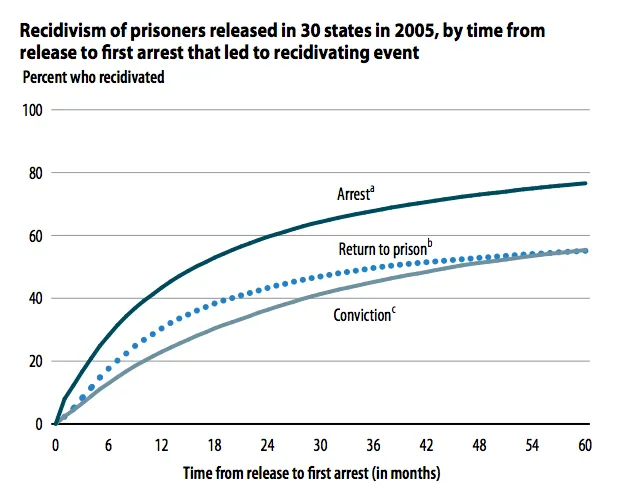

Recidivism, the rate at which former inmates run afoul of the law again, is one of the most commonly accepted measures of success in criminal justice. Nationally, the numbers are discouraging. About three-quarters of inmates released from state prisons are rearrested within five years of their release, and 55 percent are incarcerated again (see figure 1).

At first glance, the upbeat coverage seemed unjustified. New York state’s overall recidivism numbers have not changed much since the mid-1990s. The state report showed recidivism actually remained stable for prisoners released between 1996 and 2010, with about 40 percent of former inmates returning to prison within three years of release. Between 2008 and 2010, the recidivism rate even inched slightly upward.

The Department of Corrections, however, called attention to the data within the data: although overall recidivism rates were stable, between 1985 and 2010 there was a 10 percent decrease in the number of former inmates returning to prison because of new felony convictions. (That drop in new felonies took place during an era of unprecedented declines in crime nationwide, but that’s another story.) Most of the returns to prison in New York — 78 percent — were triggered not by fresh offenses but by parole violations, such as failing drug tests or skipped meetings with parole officers. In other words, the numbers showed a decline in danger to the public.

The way New York corrections officials extracted good news from not-so-good news illustrates the fact that recidivism, though constantly discussed, can be widely interpreted — and misinterpreted. Below, a few reasons why.

What is recidivism, anyway?

In some studies, violating parole, breaking the law, getting arrested, being convicted of a crime, and returning to prison are all considered examples of recidivism. Other studies count just one or two of these events as recidivism, such as convictions or re-incarceration.

When the federal government calculates a state’s recidivism rate, it uses sample prisoner populations to tally three separate categories: rearrests, reconvictions, and returns to prison, all over a one- to five-year period from the date of release. In contrast, a widely cited 2011 survey from the Pew Center on the States relied on states’ own reporting of just one of those measures: the total number of individuals who returned to prison within three years.

Both the federal and Pew statistics leave out an entire group of former prisoners: those who break the law but don’t get caught. That’s why some recidivism research, like this UCLA study on the relationship between meth use and re-offending, relies on subjects’ self-reports of illegal activity.

Another inconsistency across recidivism studies is the period of time they cover. Though three to five years is considered the gold standard, many studies examine a much smaller time frame. One recent study claimed that a parenting program for prisoners in Oregon reduced recidivism by 59 percent for women and 27 percent for men. But the study tracked program participants for only a single year after they left prison. The likelihood of reoffending does decrease after one year. But according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, an additional 13 percent of people will be rearrested four years after their release.

Who recidivates? (Yes, that’s the verb they use.)

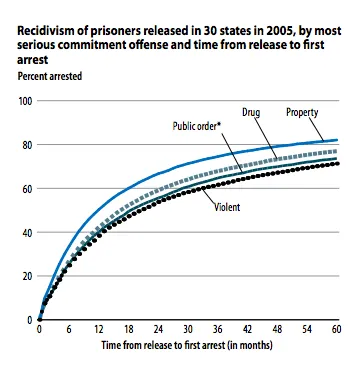

Here’s another surprising fact: The most violent prisoners are actually the least likely to end up back in jail. And they’re very unlikely to commit the same crime again (see figure 2).

One percent of released killers ever murder a second time, while over 70 percent of robbers and burglars commit the same crimes over and over. According to criminologist Robert Weisberg of Stanford Law School, robbers and burglars tend to be career criminals for two reasons: First, their offenses are likely to be crimes of skill, not crimes of passion. And second, their jail and prison sentences are shorter, so they are younger, healthier, and more able to commit subsequent crimes upon their release. People convicted of murder, on the other hand, are often elderly and in poor health by the time they have complete their sentences.

What about selection bias?

That parenting study in Oregon cited above may have been flawed, but at least it used a control group. Other research into the impacts of various social programs on recidivism is plagued by the problem of selection bias.

The Bard Prison Initiative offers liberal arts college classes to inmates in six New York facilities, and has been celebrated by Gov. Andrew Cuomo for its 5 percent recidivism rate, a figure generated by the program’s internal research, which did not study a control group. But Max Kenner, the founder of the Bard initiative, says he does not consider low recidivism the best marker of his program’s success. “If our recidivism rates stay so low, I start to worry that we’re not taking suitable risks,” he says; the program might just be cherry-picking the inmates most likely to succeed after prison. “When we do admission, we take risks on people…. How far can we push the envelope? That should be our business — getting people who are bright and interested involved in various ways. If we’re not failing at all, we’re not risking enough.”

Did the Supreme Court misinterpret the data?

In its 2011 Brown v. Plata decision, the U.S. Supreme Court cited California’s stratospherically high recidivism rates (according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, close to 70 percent of former inmates in the state return to jail or prison within three years of release) as evidence that California prisons do not rehabilitate, but instead “produce additional criminal behavior.” The justices blamed recidivism on overcrowding and the lack of adequate medical services behind bars, and ruled those conditions unconstitutional. The ruling required California to decrease its prison population.

But what if the court’s take on the causes of California’s high recidivism rate is wrong? What if it isn’t primarily prison overcrowding that causes reoffending, but an overly punitive parole system — the same trend that drives the majority of recidivism in New York?

That’s what the data shows. Parolees in California are actually less likely than parolees in New York or Illinois to commit a new crime. Yet they are exponentially more likely to be arrested and sent back behind bars for violating the conditions of their parole, according to an analysis of BJS data from researcher Ryan G. Fischer. California law punishes technical parole violations with a few days to four months in a county jail or state prison.

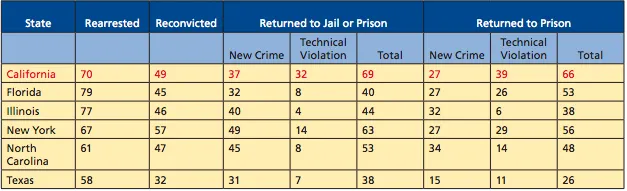

As the chart below demonstrates, using federal recidivism data for inmates who left state prisons in 1994, parole violations accounted for the entirety of the gap between California’s recidivism rate and the recidivism rates of other large states. In other words: Because of the differences in how states and localities enforce parole, recidivism rates tell us little about the reoccurrence of the types of crimes with which the public is most concerned: crimes that have a victim.